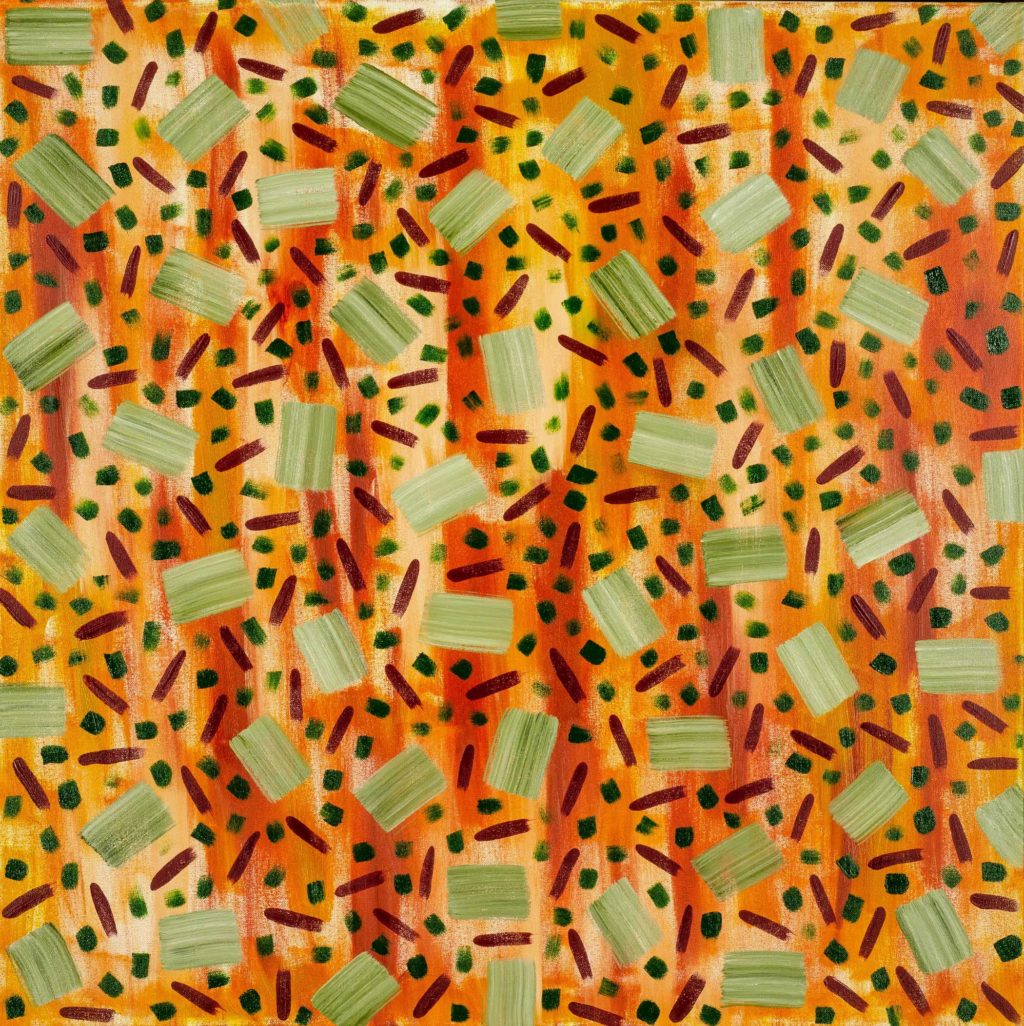

Good Earth on the Farm

Oil on Canvas

The corn stalks were so high they reached the sky, or so it seemed to a young boy spending his summers on his grandparents Colorado farm.

“Can you hear that sound?” My older sister Carla asked? I jumped up and listened intently in the direction she was facing. Nope; and back to the old metal truck I was playing with in the gravel pile near the farm’s wash house, which was often a favorite hiding spot when we played hide and seek. There was an old wringer washing machine in there and on the walls hung old wash boards and washing tubs which my grandmother used before she got an electric washing machine. For the cold winter there was a potbelly stove in the corner, an overflowing coal bucket sat next to it replete with coal dust, scattered on the floor. Clothes lines, crisscrossed the inside, from wall-to-wall, for hanging clothes to dry, on windy dusty days or during winter storms. For some odd reason there was a pinball machine almost in the middle of the room, as far as I know it didn’t work. I’m sure my grandma used to stack folded laundry on it. I vaguely remember that my older cousin Donny, scrounged it somewhere, put it in my grandpa’s truck, brought it to the farm, moved it into the wash house, and there it sat.

My sister jumped up again from her squatting position, she had a stick in her hand, just making designs in the gravel pile, near where I was play-plowing with my metal toy plow. She had to squat because she was wearing a sundress. Me; I almost always wore grandpa jeans, or at least that’s what I called them, they were bib overalls, the denim kind. Usually no T-shirt and of course my high top Keds. “Nope I still don’t hear anything,” I replied. This time she was adamant, “Get up and listen. I don’t want to miss this one Rod!.” Secretly I had to agree I really did want to hear what she was listening for.

The farm was laid out like a compound surrounded by dirt. There were some trees that provided shade in the summer and a little grass area next to the main house. There was a coal shed next to a row of garages. Neatly tucked away next to the coal shed was an old wooden stump with a very rusty ax stuck in it. This was where many of a Sunday chicken dinner started. “Off with its head” my grandpa would say, as he chopped off the chicken’s head, and then on its way to a wash tub filled with hot water for proper plucking. My grandpa always flung the chickens head over the fence, and within minutes it seemed, this old rusty colored cat showed up for a private feast. On the other side of the open area; three small buildings stood, first was the wash house then came a rather large chicken house, complete with grain bin and lots of nests for chickens to lay eggs in. Early in the day my grandmother who always wore a house dress and apron, grabbed her basket, headed for the chicken coop to collect fresh eggs. When she headed back to the house she was muttering in her native tongue: Slovenian. As was often the case, a bold chicken pecked her forearm as she retrieved the eggs. Even though I didn’t understand what she was saying, it was easy to figure out that there was a chicken destined to become a Sunday dinner, and the execution would be eminent, if my aunt and uncle were coming out to the farm for dinner.

There was a pigpen, although it rarely housed pigs. A large machine shop and tractor garage was on the other side in a large open area, that had some old wagons positioned between various fruit trees my favorite was the cherry tree.

My grandpas old red truck sat in one corner of the compound that I often played on, in fact the whole farm was just one big playground for a young boy.

My sister jumped up again, and I quickly jumped too, because I could hear it loud and clear. Off we went running passed the chicken coop; past the pigpen; past the old red truck, and through the gate, and out into the cornfield. It was well into summer and the corn stalks were just about as high as they were going to go, waiting for the fall harvest. It was difficult to run through the cornfield. There were big clods of dirt between the rows, easy to trip on, and the field was being irrigated, so there were pools of water that you had to carefully navigate around and sometimes jump over so you didn’t step into a muddy water puddle.

Big jutting leaves that nurtured the corn while it was growing, would stick out like arms and hands and brush against your body, almost as if it wanted you to be confined or at least to give you a hug.

All you could see around you was the whitish clay like dirt below your feet, darkened in spots by the moisture from the crop quenching irrigation water. The neatly planted, mid to dark green walls of corn surrounded you. Above was a beautiful deep blue sky, that contrasted magnificently with the tops of the shimmering and swaying corn silk fibers, that when fresh would catch the afternoon summer breeze.

My sister and I ran as fast as we could laughing and shouting, it seemed like we were running forever and the noise was getting louder and louder: Soon we would be able to see large billowing black smoke filling the sky off to the right of us. “Run, run as fast as you can, we don’t want to miss it.” my sister shouted. I ran and ran, I did… for a young boy this was a thrill. Something I would never see back in the mountains where I lived in California.

It was getting brighter as the last rows of corn were coming up, and before us was the irrigation channel that carried water to all the farmers so they could water their crops. That channel marked the end of our frantic journey.

We both stood there in total awe, looking up at this big, or should I say giant black locomotive,with so many iron wheels, running at full speed, billowing tons of black sooty smoke into the air. We started waving frantically and making the gesture to the engineer, to pull on the lanyard so we could hear the loud train whistle. And he complied with grin on his face and a friendly wave to us kids, and then he laid on that whistle until the sound faded off into the distance. We stood watching the train until the very end. Sometimes counting the cars, waiting for the caboose to show up, and more often than not there was somebody in the cupola, he gave us a wave and a smile, which he had to do countless numbers of times to all the farm kids as the train made its way through the croplands, heading to far away places.